❉ David L. Snyder discusses his work on such cult classics as Blade Runner, Bill And Ted’s Bogus Adventure, Strange Brew, Demolition Man, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and much more besides.

Production Designer David L. Snyder has worked with some of the very best filmmakers on some of the most distinctive and influential films from the last 40 years. We Are Cult’s Nick Clement had the fabulous honor of conducting an email interview with Snyder, where they discussed his background, influences, favorite films, working with Ridley Scott on his seminal masterpiece Blade Runner, his ahead-of-its-time work on the sci-fi cult classic Demolition Man, what might’ve been the end result of Soldier had some different things gone down, his work on the beloved ’80s classic My Science Project, his love for cinematic comedy, what he has coming up in the future, and so much more…!

Thanks so much for taking the time to answer some questions, David. This is very exciting. Where does your passion for art direction and production design stem from? Did you love movies as a child?

Snyder: As a kid from, from when I was five years old to about 20 years old, I went to the movies every Friday night, and Saturday and Sunday matinees. I never played sports. Beginning with the 1949 10th Anniversary issue of The Wizard of Oz, which is the first film I saw in my memory, we went to the ‘show’ as we called it, no matter what was playing. It just so happens that my Kensington neighborhood theater in Buffalo, NY, played MGM Studio’s output. I was highly influenced by the films produced by the Freed Unit (Arthur Freed) like Singin’ in the Rain, On the Town, The Band Wagon, High Society and dozens more. I had no idea that the way these films looked was the dominion of the MGM Studio art department. I had no idea that ‘art director’ was a job classification. What I do remember was that I was so enchanted with the way the settings seemed to jump off the screen, and with the dancing and the music that I hardly paid attention to the plot. Then there was the glamour of it all. Hollywood. The irony is that I have never designed a screen adaptation of a Broadway show. Still hoping.

Do you approach your job differently depending on the genre you’re working within? Do you have a favorite genre to play in?

Snyder: Absolutely. Unlike the era when I began my career near the end of the studio system, each studio had a signature style dictated by the heads of the art departments. Cedric Gibbons at MGM; Van Nest Polglase at RKO; Anton Grot at Warner Bros.; Lyle Wheeler at Fox; Stephen Goosson at Columbia; Richard Day at United Artists, and Hans Drier at Paramount. Each one of these art directors had a signature style of their own design aesthetic that dictated what their studio’s films would look like. I have no particular design style that I impose on my work. I consider myself to be a designer of films, not sets. I‘ve always thought of myself as being a designer of ‘pictures’ based on the ‘words’ I read in the script. In review of my 40-something movies it appears that they were all designed by different art directors and their teams. Good. That brings me to the next answer and yes, again, when I put an art department together it’s like ‘casting’. There are certain illustrators, set decorators, set designers, and props people that I assemble based on the genre of the film. Although I am principally noted for science-fiction and comedy, films like Racing with the Moon, a WW II dramatic period piece, is something that was very rewarding for me. I just want to make the kind of visual entertainment that I’d buy a ticket to see.

Is there anything you’d like to attempt in the future that you’ve yet to explore?

Snyder: If I could choose a genre for a future film it would be an adaptation of a Broadway musical, which would be a fond reminder what it was like in my early days on television variety shows. Very thrilling to have a live band / orchestra working with talent like Olivia Newton-John, ABBA, Andy Gibb, Debbie Reynolds, Aretha Franklin, Nelson Riddle and more. A live audience and the stage manager’s countdown to going ‘live’ On-The-Air… Exciting stuff. I must say, I miss those days.

What’s been your favorite film that you’ve had the chance to work on?

Snyder: Hands down, I’d have to say Back to School. Hanging out with director Alan Metter, Harold Ramis, Sam Kinison, and Rodney Dangerfield – I mean – are you kidding? We had a great time beginning at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, ending up with a gala premiere at the Ziegfeld Theatre in NYC. We built the entire dorm room on stage at the Culver Studios, we had Oingo Boingo playing at the dorm party, the cast was perfect and I recruited my Blade Runner set decorator Linda DeScenna to dress the sets. It was a super hit that earned nearly $100 million on a budget of just over $10 million and it was #1 in video sales & rentals the day it was released. It’s still considered to be one of the highest grossing films in the history of Orion Pictures. I remember I was working with Carl Reiner on Summer School when it hit the charts. Even Carl Reiner was stunned.

Are there other Production Designers you look up to, or are you a fan of the work of someone in particular?

Snyder: Just about anyone from 1920 – 1970, the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood, designers like Henry Bumstead, Preston Ames, Robert ‘Bob’ Boyle and Harold Michelson are those that I knew. As for today, John Myhre, who won an Oscar for his work on Chicago; Richard Hoover, who does films, television and Broadway; 2-time EMMY winner Howard Cummings; and of course Dean Tavoularis, the designer of most of Francis Ford Coppola’s films. I must also mention William Cameron Menzies, who is arguably the greatest of all. He designed Gone with the Wind.

Your mentor is Lawrence G. Paull. How was this connection made?

Snyder: I was a staff art director at MCA-Universal Studios. There were 35 movies and TV shows filming on the lot. The Blues Brothers, 1941, and Larry was designing In God We Tru$t, starring and directed by Marty Feldman. I was ‘assigned’ to work on projects by the head of the art department and I became kind of a show ‘doctor’ who was sent in at the last minute to fix problems, on shows like Buck Rogers In The 25th Century, The Hulk, and Galactica 1980. Larry was looking for a new assistant and we met on the recommendation of the studio production department. We hit it off and began a life-long friendship and it led to my hiring as the art director on Dangerous Days, aka Blade Runner.

Let’s talk about Blade Runner, because obviously that’s one of the cornerstones of your career. Can you describe what it was like to collaborate with Ridley Scott, Douglas Trumbull, and Syd Mead?

Snyder: I learned a lot from people I considered to be at the top of their game. Ridley as a director with a great interest in the visual aspects of his films; Doug Trumbull who is more mechanically inclined in his brilliance and the talented Syd Mead who is more of an industrial designer and superb illustrator than a filmmaker. In my learned opinion Syd’s international fame and his remarkable genius may have cost Blade Runner the Oscar© due to the fact that he, not being a member of the Art Director’s Guild/Union received the majority of the press heaped upon the films unique design. Praise that in fact belonged to Lawrence G. Paull, the films’ production designer. I never thought that Syd was instrumental in the way the press and the studio handled the publicity. It was just the fact that Syd was internationally renowned. It was our Oscar winning producer, Michael Deeley (The Deer Hunter) who stated in a 2007 interview, “To be fair, if anyone deserves the credit for the look of Blade Runner it’s Ridley Scott,” which is a fair appraisal.

Why has Blade Runner continued to hold its place in the history of cinema after all of these years?

Snyder: Because there was nothing like it before we made it and it was the last of the analog pre-CGI science-fiction films. Aside from those who never got it, at the end of the day it’s basically a love story and what it’s like to be a human (or not) under all those gritty layers of Los Angeles 2019 AD.

Have you had the chance to see Blade Runner 2049 yet, and if so, what did you think?

Snyder: Yes. In a few words, Blade Runner 2019 is Act I, and Blade Runner 2049 is Act II. I thought it was brilliant in IMAX 2D. If Dennis Gassner wins the Production Design Oscar©, I’d feel personally rewarded.

You worked with Taylor Hackford on his musical biopic The Idolmaker as the Art Director – what was that like?

Snyder: Larry Paull recommended me to Hawk Koch who was producing with Gene Kirkwood. Unknown to them at the time I had been an on-the-road rock ’n’ roll drummer during the same time period as the film. During my interview I noted that the script’s titular character reminded me of someone I knew during my days in the band, Bob Marcucci. Stunned, the producers said “Wait a minute” and sent someone to get the Bob Marcucci to introduce us. That’s how I got the job, I think, and I designed it out of my experiences and my brief music career scrapbook. My credit as Art Director is a reflection of changing times. The Production Design title was just coming into vogue. I was the principal designer.

Another Art Director credit appears on Brainstorm, which is one of my favorite sci-fi films from the 1980’s. How did that come about and what can you say about that job?

Snyder: I had met with C.O. ‘Doc’ Erikson, an executive on Blade Runner who was producing Fast Times at Ridgemont High with Amy Heckerling directing. I had a great meeting and when I arrived home I got a direct call (no secretary or assistant) from Doug Trumbull offering me a job to replace the art director on Brainstorm. John Vallone, the production designer was a friend and he was O.K. with me coming on board. How could I say “no” to my Blade Runner colleague who was soon to be my Oscar© co-nominee? I said “yes” and within an hour I got a call from ‘Doc’ Erikson that Amy agreed to hire me on Fast Times. Never really got over it, however having gotten to work with lovely Natalie Wood, as tragic as it ended, was worth it.

You have a couple of fun movies where your work apparently went uncredited – Miracle Mile and Deep Blue Sea – both of which have a passionate fan base. What were your contributions to these movies?

Snyder: I met Steve De Jarnatt on Strange Brew, which he had written with Dave Thomas and Rick Moranis. Sometime later I began working with Steve (pro-bono) on Miracle Mile waiting for financing. I didn’t have much to contribute beyond location scouting, and my agent at the time, Phil Gersh, put me to work on another picture. I still consulted with Steve, as we were friends and eventually Chris Horner and Richard Hoover, whom I greatly admire, designed the film. On Deep Blue Sea, Warner Bros. Production Department hired me to put together a presentation for the studio. When it was completed, one writer and I did the ‘pitch’ to Mark Scoon, Lorenzo di Bonaventura, Jeff Rabinov and Akiva Goldsman, and it was greenlit. When Renny Harlin was hired to direct I was already at WB working for Jerry Weintraub on Soldier. In the end, all of my designs were universally ignored by Mr. Harlin – Ha!

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is one of the most exuberant films of all-time, and a movie I have seen countless times. What was it like working with Tim Burton on his break-out picture?

Snyder: Tim and I met in the Old Animation Building at the Walt Disney Studios in 1984. He was doing Frankenweenie and I was designing My Science Project. When Tim was hired to direct Pee-wee I guess I was the only production designer that Tim knew, and his designer of Frankenweenie, Rick Heinrichs, was not acceptable to Warner Bros. Production Office due to his lack of experience. Of course Rick went on to win an Oscar© for Sleepy Hollow. We had a mere $6 million budget for the entire production and we were basically under the WB radar as The Goonies was the big show on the lot with triple the budget. We were in a bungalow with writers Phil Hartman, Michael Varhol and Paul Reubens, along with my Strange Brew storyboard artist Paul Chadwick, who went on to a career at Dark Horse Comics. The theme of the movie was “If it ain’t bright, it ain’t right,” which was coined by set decorator Tom Roysden. It was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had and I was invited to MoMA in NYC to introduce the film at the Tim Burton Retrospective in 2009. Danny Elfman’s music was so good that I brought him to Alan Metter, director of Back to School, not only as composer, but with his band Oingo Boingo.

Strange Brew is the very definition of “cult-classic,” and I’m wondering how your involvement on that film came about.

Snyder: Following my days on Brainstorm, I was invited to meet Dave Thomas and Rick Moranis in their MGM (now SONY) offices by Jack Grossberg who had come in to complete the film following the death of Natalie Wood. Jack was hired by MGM and Freddie Fields to produce Strange Brew and as he was happy at my completion of Brainstorm with Doug Trumbull. He invited me to the Great White North to design the film. To this day, I see Dave, cameraman Steven Poster, ASC, Editor Patrick McMahon, and associate producer/AD Brian Frankish for an occasional ‘reunion’ dinner at Musso & Frank’s. We’re planning a screening in the near future.

My Science Project was one of my go-to selections as a kid on VHS. It’s as wild and woolly as that sort of low-budget filmmaking can get from that time period. What were your experiences working on this beloved film from my childhood?

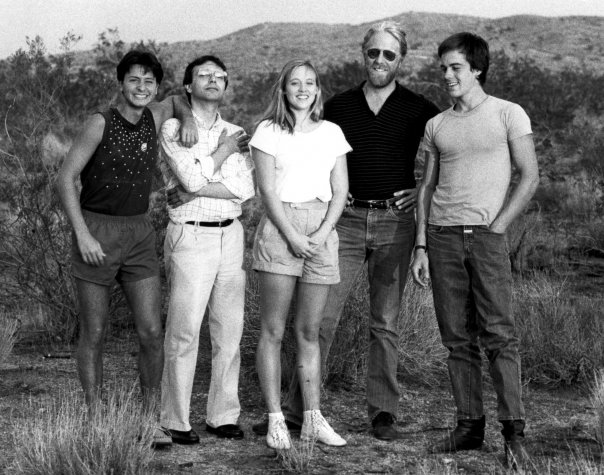

Snyder: I interviewed with Jonathan Betuel and Jonathan T. Taplin at Disney. I was hired the next day. We had great offices in the Old Animation Building and I was invited to casting sessions where I met longtime pals Raphael Sbarge, Fisher Stevens and Danielle von Zerneck (La Bamba). We had a $4 million budget and I spent plenty of it on sets and brought in my special effects supervisor Michael Lantieri, who later won an Oscar for Jurassic Park, to ensure continuity with the ‘action’ settings, such as Dennis Hopper’s science classroom. We shot at the lot on stages and locations in Arizona.

It’s not quite as good story-wise as Betuel’s The Last Straighter, but Davy Walsh’s camerawork and John Scheele’s brilliant dinosaur business made it a fun ride. Dennis Hopper: A trip.

Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey was so unlike the original film in so many ways, and on a visual level, it’s rather amazing to think about. How did you get involved?

Snyder: Well, I think I was hired because I ‘passed’ on the first Bill & Ted film. Hollywood’s funny that way. Pete Hewitt is a talented artist in addition to being a writer-director and it helps when a director has a vision. The nightmare sequences are some of my favorite sets up there with Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. Forced perspective sets and the giant gargoyle head and its miniature counterpart are pretty accurate and play well to the comedic scenes. The crew consisted of many Blade Runner veterans and you can’t get any better than that. Not a fan of the ‘Station’ bits, but Billy Sadler as the Grim Reaper steals the movie.

Super Mario Bros. was one of the first video-game movies ever made, and it’s been detailed elsewhere that the film had some big-time production and post-production problems. What was your experience like working on that movie?

Snyder: In 1993 I interviewed with directors Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel to replace production designer Wolf Kroeger with whom the directing team had encountered creative differences. They in turn had replaced original director Greg Beeman. I have to say it was chaotic from the start. The original script by Dick Clement and Ian La Franais (The Commitments, The Bank Job) was very ‘dark’ and amazing. It was the script that Bob Hoskins and Dennis Hopper had signed on for. As the design process went on with an extremely talented art/construction/set decoration/creature staff, the re-writes began in earnest when Jeffrey Katzenberg flew into Wilmington on the Disney G4 and swooped up the rights in what was moving forward into a bidding war with rival studios.

It was a smart move on Disney’s part considering the obvious bonus of Nintendo characters being spattered all over their theme parks including Tokyo Disneyland in Japan, which is home to Nintendo. By the time we began filming, there was another major ‘change’ as Dean Semler, ACS ASC, director of photography, fresh off an Oscar© win for Dances With Wolves was brought in to replace his predecessor. I must say that in my experience my sets are all designed in concert with the cameraman’s requirements in mind. Lucky for me and my staff that Dean understood that he was going to accept the way the sets were constructed and decorated. He was great to work with and hardly ever asked the art department for anything beyond reason.

The biggest problem, out of many, was with the revisions in the script and schedule overruns, which caused budget problems that caught up with us when we ran out of money to shoot a proper ending which was the final battle between Mario and Koopa. Dinohattan. In spite of all the efforts of visual effects director-designer-producer Christopher F. Woods, we just couldn’t find the money to complete the battle as written and storyboarded. With all the effort that had gone into Dinohattan aka Koopaville, the story just never came together. Not even with extensive and expensive added scenes shot in Los Angeles months later following a screening with Michael Eisner and Jeff Katzenberg on the Disney lot. After the screening, Michael and Jeffrey congratulated me on the sets and I was dismissed. Producer Fred Caruso, production manager, Robert D. Rothbard and Rocky & Annabel stayed behind for the meeting that led to the filming of the added scenes. If it were up to me I believe there would be a better film to be made by ‘lifting’ some scenes. I did the Blu-ray interview for the Second Sight Films release in 2104, and I was finally able along with my colleagues to look back on the experience of making the film and the disappointment of its failure on one hand and its current cult status on the other. My takeaway from SMB is the lifelong friendship I went onto with Bob Hoskins until his untimely death. Bob and I went on to do 3 films together, one which he directed, Rainbow, the 1st digital to 35mm theatrical film. Another colleague I admired as much as Bob was Gene Wilder. My fondest memories of my time in the Industry are my years with Bob and with Gene & Gilda (The Woman in Red). All three brilliantly unique.

On Super Mario Bros. you were also credited as being the Second Unit Director. How did that job extension take place, and do you like taking on that responsibility?

Snyder: Near the end of principal photography it was decided by the creative team including producer Roland Joffe that the rural beach city of Wilmington, NC was not going to look like Brooklyn, NY with the exception of the urban downtown shopping district. Therefore I was dispatched to New York along with assistant director Robert D. Rothbard and a camera crew to film some wide establishing shots of Brooklyn neighborhoods including the Bridge and the World Trade Center across the River. We had the Mario Bros. plumbing truck shipped from Wilmington to New York City via a car carrier. We shot from sun-up to sun-set and had dinner at Patsy’s on Fulton Street. The ‘job extension’ earned me a Director’s Card in the Directors Guild of America. I went on to direct 2nd Unit on The Whole Nine Yards and others.

Demolition Man was so ahead of its time both thematically and visually. I’d love to hear anything about the making of this 90’s classic.

Snyder: In another case of replacing the designer on a film, (full disclosure: I’ve been replaced) I took over on Demolition Man following a dispute between the director, Marco Brambilla, and his original production designer. Producer Joel Silver knew of my design work on Super Mario Brothers due to his uncredited involvement in the Coen Bros. film The Hudsucker Proxy which was also shot in Wilmington, NC. I don’t know if he ever came to the set, but word gets around on distant location shoots. I signed on at Warner Bros. and I ‘ash-canned’ all of Victorian-era-of-the-future sets designed by my predecessor in line with the vision my director Marco had communicated to me. I also wisely brought along my Super Mario Brothers 1st assistant director, Louis D’ Esposito, who had steered us all through every bump in the road on that picture. (Louis is now Co-President at Marvel Studios).

The design budget was $1,250,000 and the sets were about $7 million when fitted with all the special mechanical effects of the Cryoprison. The art department was divided into VFX, picture cars, sets, action props, production illustrations & storyboards, and visual effects art direction. Major talent, all. The biggest reason for my interest in Demolition Man was having art directed dystopian Los Angeles for Blade Runner – this was an opportunity to design a futuristic utopian L.A. / San Angeles in contrast. The thing I remember most about the notoriously irrepressible Joel Silver is what he said to me in the first production meeting with all producers, heads of department, their assistants, WB production staff and the director. “You know David, with the kind of money you’re talking about spending we may as well just have you build a space ship and take the cast and crew into the future!” We also got great camera work by the late Alex Thompson, BSC, ASC.

Soldier is another film that had a challenging production, but on a visual level, it’s absolutely astonishing at times. I’d love to know about your approach on this film, the connections it has to Blade Runner, and why you think the movie missed the mark with critics and theatrical audiences.

Snyder: Soldier was my eighth film on the Warner Bros. lot which always felt like my home studio. I actually did Soldier twice. We started pre-production in 1995, and when Kurt Russell agreed to star his one deal point was that he be given a one-year prep time to build up his body for the role. The studio agreed. At the same time producers Jerry Weintraub and Susan Ekins called me in to inform me that while we waited for Kurt we’d been offered an opportunity to take over the production of Vegas Vacation. We did. We returned to Soldier in 1997 right after I did the concept design and ‘pitch’ for Deep Blue Sea. Paul W.S. Anderson took a keen interest in the design of the film which I was delighted to accept. This film is the most expensive design and build I have ever done. $10 million in sets (we came in $80,000 under budget) before they were decorated, propped and mechanical special effects were included. We built an entire off-world environment on WB Stage 16 (the same stage as the Cryoprison from Demolition Man) and had additional sets on stages 25 & 26, with seven stages in total and the Barker Hanger at Santa Monica Airport. The wreckage of the Pandora was 120’ long and four stories high. There was one art director, Paul Sonski, whose entire job on the run of the show was that set near the Fontana, CA stone quarry.

Remember, this is 1997, and all set construction drawings, production illustrations (some painted and some in ink), and storyboards were all done 80% by hand. Very few computer generated images, which made pre-production time for the art department staff very extensive.

The studio had set a hard release date for the film so the main set, the Pioneer Village, was constructed 24/7 with three crews working in eight hour shifts under the supervision of construction coordinator Joseph E. Wood – a formidable task even for someone with his experience. The crews worked every day with the exception of Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day. There were many WB visitors to that massive set. Clint Eastwood, Ray Romano, Phil Rosenthal and many others who were working on the WB Lot. Plenty of domestic and foreign press too. In my opinion, the film’s failure ($60 million dollar production budget plus P&A with only a $14 million domestic box office tally) was in some respect due to the director’s decision to ‘realize’ the more graphic scenes of brutality in the David Webb Peoples’ script, which seemed to be Paul’s particular way of pleasing his core audience as he did in Event Horizon, Alien vs Predator, and Mortal Kombat. I have to say that Paul’s been very successful with his films, so what do I know? His partner, Jeremy Bolt, was a good ally who kept everything in balance creatively and financially for Jerry Weintraub. WB tried to market it as an ‘action’ picture but all the time we were making it, I thought it was Shane in outer-space. Yes, there’s the ‘sidequel’ connection to Blade Runner. I tried to make it visually obvious with the recreation of Syd Mead’s Spinner as wreckage from the past. The take-away is that I loved working with cinematographer David Tattersall, ASC, and I believe there is a good movie in the footage. It needs a re-cut although I doubt it will ever occur.

An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn is one of the oddest movies ever, a film about the legendary fake-director Alan Smithee, where the film’s actual director, Arthur Hiller, tried to have his name removed in favor of the trickery that the film is all about. After Arthur Hiller had his credit changed to Alan Smithee, the Director’s Guild of America unregistered the name Alan Smithee. This is the last film to ever bear that pseudonym. Any comments? I’m still fascinated by the entire production.

Snyder: I was hired by Fred Caruso and Ben Myron whom I worked with on Super Mario Brothers. Joe Eszterhas wrote an amazing Hollywood ‘insider’ script that was rumored to be a favorite of Steven Spielberg’s. Because Arthur Hiller had been the president of the AMPAS, it was assumed that he would be able to get anyone and everyone in the business to agree to appear in the film at SAG scale. Well, Arthur was good at that, but unfortunately, he and Joe could not agree on the artistic direction of the narrative, causing Mr. Hiller to take his name off the picture. It was a lot of work and a lot of fun to create a 75 year-old studio, Challenger Pictures, and its complete history with the aid of legendary Hollywood historian Marc Wanamaker. We built the executive offices, the executive dining room and executive conference room. Unfortunately for my design team and me, Arthur made a decision to shoot it documentary-style, and for the most part, the film is a series of talking heads. Famous talking heads mind you, as this was the most star-studded film I’d ever worked on. You won’t see much of the sets that were stunningly decorated by Claudette Didul (Mad Men) but you will see Billy Barty in his final film and Harvey Weinstein in his only dramatic role I know of as an Anthony Pellicano-type P.I. The person I felt the most sorry for was Monty Python legend Eric Idle, who had the title role. He said in various interviews meant to promote the film that “this is rather dreadful.” Thank the Gods for Spamalot, yes?

I’d love to hear a bit about your newest project, “Into The Rainbow” aka “The Wonder 3D” aka “奇迹:追逐彩虹” / “The Wonder: Chasing Rainbows,” which was filmed in Mainland China and New Zealand

Well, first of all, everywhere we went in China (Beijing, Shanghai and Qingzhou) it was like a parallel universe of the great cities of America and Europe, except the citizens were 98% Chinese. The people love American culture – films, music, television, and even the advertising features ‘western’ models and products. There’s KFC, McDonalds, and everything else in between, not to mention every product from the U.S. is consumed on a massive scale. Our film starring Willow Shields (The Hunger Games’ Prim) is scheduled to open on 32,000,000 screens via China Film Stellar, our Chinese exhibitor.

The camera crew was from Peter Jackson’s stable in New Zealand, and our cinematographer is Richard Bluck, NZCS, ASC. The film was shot in 3D with Red Dragon cameras using the WETA / Wingnut mount system. My art department was as talented as any I’ve ever worked with and when the Chinese build sets, they seem to be built for an eternity, and not just as scenery. We filmed at the Laoshan Tea Plantation and for the urban settings we filmed in Qingzhou, a town that goes back beyond the Ming Dynasty, and yet it has been rebuilt to appear as it did centuries ago, almost like a studio backlot. This urban renewal program became common in China as the economy exploded. The Bullet Train between Beijing and Qingzhou was amazing and something we should have here in America. Into The Rainbow is a teen fantasy-adventure featuring teen mega-star Wu Leo, Taiwanese star Joe Chen, Chinese-American TV star Archie Kao, Chinese-New Zealand star Jacqueline Joe (Top of the Lake) and Italian star Maria Gracia Cuccinota (Il Postino) as the evil scientist. We just held the U.S. Premiere of the film at the Savannah Film Festival on November 3rd and our star Willow Shields was honored with the Rising Star of the Year Award. Into The Rainbow was the first official tripartite film production between the Peoples Republic of China, The United Kingdom and New Zealand. It took nearly five years in development due to the requirements of the CFCC and the SARFT whose job is to provide the rules of finance, censorship, and distribution. This was a difficult situation that Hollywood producers and studios are only beginning to understand. I’m looking forward to returning to China for several films in our development ‘bin’ with partners Robert and Ashley Sidaway, writers-producers of Into The Rainbow at Friendship Films, Ltd. = More information can be found here: https://friendshipfilmsltd.wordpress.com/

❉ Nick Clement is a freelance writer, having contributed to Variety Magazine, Hollywood- Elsewhere, Awards Daily, Back to the Movies, and Taste of Cinema. He’s currently writing a book about the works of filmmaker Tony Scott, and co-operates the website Podcasting Them Softly.

❉ He is also a regular contributor for MovieViral.com, a site dedicated to providing the best news and analysis on viral marketing and ARG campaigns for films and other forms of entertainment.