❉ Will Brooker looks at the continuity of Bowie’s work through the prism of his recurrent themes.

I’ve been a dyed-in-the-wool David Bowie fanatic for 30 years now, and it seems that I’ve been reading about Bowie for as long as I’ve been listening to him, and its testament to my abiding interest in The Dame that not only do I possess a raft of vinyl and CD, but also a heaving bookcase of weapons grade Bowieology.

When you come across a cultural hero who captures your imagination, it’s not enough to simply gorge yourself on their work – you want to take a peek under the hood, learn a little about their past history, what makes them tick, what turns them on, and compare your solitary assessments of their work to other people’s own interpretations.

Nowadays, we have this thing called the internet which allows you do all of the above at a few keystrokes, although what it brings up lacks any real discrimination, source-wise. Thirty years ago, it was incumbent on the fan to do all the heavy lifting in order to look beyond the work for biography, discography, commentary and analysis. And thus, I would lose myself in WHSmith’s rock and pop section and rampaged through my local library’s reference section to devour the rich seam of Bowieography that could be found in its hallowed halls.

Growing up as a Bowie fan in the ‘80s, there was no lack of literature available covering the Main Man’s life, times and recorded works, and the bibliography in print at this time offers a snapshot of the changing face of rock writing: Bowie’s life was first condensed in paperback form by George Tremlett’s The David Bowie Story (1974), a Futura paperback which sat comfortably on the shelves alongside similar volumes devoted to Elton John, David Essex and the Bay City Rollers, a brisk, accessible biography that effectively cut and paste press releases and news clippings; the first ‘fan’ biography appeared two years later with Vivian Claire’s breathless and well-illustrated David Bowie! The King of Glitter Rock (1977).

Come the 1980s and the range of Bowie commentary in mass market book form broadened: Controversial cult publisher Savoy Books’ David Bowie Profile (1981) by Bowie’s former press man Chris Charlesworth, was liberally illustrated with rare photos and extensive quotes from the man himself and boasted the first bootleg discography, while Charles Shaar Murray’s An Illustrated Record (1981) raised the bar for providing a record-by-record overview of the first 15 years of Bowie’s career that was not only insightful and informed but also cheerfully flippant and irreverent, an approach that Bowie himself approved of; the global success of Bowie’s Let’s Dance phase saw Bowie books become big business, with Peter & Leni Gillman’s Alias David Bowie lucratively serialised in The Sunday Times and attracting Bowie’s scorn for delving into the Jones family’s history of mental illness, former MainMan press officer Tony Zanetta’s Stardust was a fairly routine walk-through of Bowie’s career that traded on Zanetta’s involvement in the MainMan empire, while Angie Bowie got loose-lipped with the gossipy Backstage Passes.

As rock journalism became an honourable trade in the ‘90s with the rise of Q, Uncut and Mojo, Bowie’s musical career was rewarded with richly researched heavyweight books focusing on his career and collaborators, such as David Buckely’s Strange Fascination and Paul Tryncka’s peerless Starman. Later on, Bowie’s “retirement” years inspired a range of books that ultra-focused on specific eras in Bowie’s career, such as Peter Doggett’s The Man Who Sold The World, Dylan Jones’ Ziggy Played Guitar and Simon Goddard’s Ziggyology. Meanwhile, actor, scriptwriter, director and Dalek Nicholas Pegg continued to dutifully update and redraft his Bowie domesday book, The Complete David Bowie – now on its seventh volume.

So it should come as no surprise that, with Bowie’s passing last year, a new era of Bowie retrospectives are upon us, aiming to assess the entirety of Bowie’s life and career now that it has the one thing that never seemed possible – a full stop.

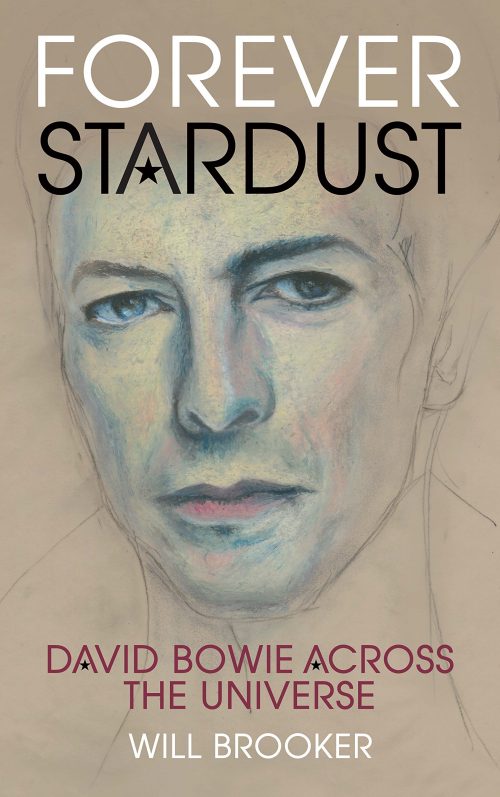

Will Brooker’s Forever Stardust is the latest addition to this Bowiephile’s already heaving bookcase, but it should be stated upfront that this is not a calculated cash-in on a beloved artist who is already being canonised as a more cuddly, populist-friendly icon than he was in his lifetime. Brooker, a Professor of Film and Cultural Studies at London’s Kingston University, first embarked on researching Forever Stardust when David Bowie was still alive, undertaking as part of his research spending a year living as David Bowie (which you can read about here).

With Forever Stardust, what Brooker has set out to do is provide an alternative to the linear biographies of Bowie, by exploring how Bowie was a far more consistent artist than many interpretations of his career would have us believe, by tracing the core themes from his final works through his incredible back catalogue.

In examining the recurrent themes and obsessions of Bowie’s work – alienation and otherness, issues of race and cultural identity, sexual politics, and questions of authorship and ownership – Brooker opts out of the traditional biographical timeline, instead looking at the continuity of Bowie’s work through the prism of his recurrent themes.

Brooker’s approach is very much a matter of personal taste, and at times feels more like a judgment than an appreciation, with buzzwords such as cultural appropriation and privilege pinging around like a round of liberal bingo when it comes to the likes of Young Americans, Loving The Alien, China Girl and the cultural hybrid of Black Tie White Noise, with Bowie’s attempts at engaging with cultural difference all too often bracketed with the phrases “well-intentioned” and “misguided”.

Personally, I feel that I think Bowie was largely to be applauded for acknowledging issues of East vs West when most white musicians remain largely insular and inwardly looking, and enriching our musical palate by accommodating and collaborating with non-Anglo music forms and musicians, from Carlos Alomar to Erdal Kizilcay, whereas Brooker’s depiction of Bowie in terms of racial and cultural inclusion calls to mind the image of a kind of Man from del Monte white plantation owner, a portrayal that also seems to deny the agency of his non-Anglo collaborators (Alomar, Kizilcay, etc.) as willing accomplices in Bowie’s cultural exchanges.

By the same token, there’s an acknowledgement in some entries that Bowie was at least aware of his ‘privilege’ and worked around it, and incorporated it into his more cynical lyrics, and Brooker is absolutely spot-on in nailing the ethically dodgy aspects of the video for Black Tie White Noise and Bowie’s cover of Don’t Let me Down and Down, with its pidgin lyrics and dodgy cod-patois vocals.

Bowie’s status as the eternal ‘stranger in a strange land’ is one of this work’s distinctive features, and that’s also tackled critically in the segments dwelling on Bowie’s identification with the ‘alien’ and neatly tied in with the luminance of his suburban childhood, which is dealt with informatively and insightfully, and this is where Brooker really hits the mark. Equally, Brooker acknowledges the inroads Bowie made in terms of mainstream acknowledgement of sexual fluidity, picks Bowie up on his mid ‘80s denial of bisexuality at a time when the AIDS crisis saw an upswing in homophobia, but also concedes the significance of Bowie’s sexual politics as having liberated so many of his fans who identified as gay, lesbian, queer or trans.

I began this review by looking back at the vast bibliography of Bowie books. There are a LOT of David Bowie books. One for every album, at the last count. There are also a lot of very bad David Bowie books. Forever Stardust is not one of them. It’s subjective – aren’t they all? – and in that respect, it’s a valid contribution to Bowieology; full of debateable and enlightening viewpoints. Don’t be put off by its’ academic gloss: you’ll come out of it knowing who Foucault, Derrida and bell hooks are if you didn’t to kick off with, and if nothing else it’ll send you back to your records and videos to challenge and question some of Brooker’s more strident evaluations or more questionable perspectives, as is only right and fitting for a lifetime’s work that is still ripe for appraisal and reappraisal “as long as there’s me, as long as there’s you”.

❉ ‘Forever Stardust: David Bowie Across The Universe’ by Will Brooker is published by I.B. Taurus.

Great review, James. And you’re very much the right man to have done it. I think this will join my similarly groaning Bowie bookshelf soon.

Shortly after Where Are We Now came out, I had a slightly similar ‘Be Bowie’ idea to Mr Brooker’s: I was going to grow my hair to Hunky Dory length, then spend the rest of my life following Bowie’s various haircuts and dye jobs, hoping to either die before I got to the Glass Spider mullet, or at least survive it with enough dignity to push through into the Blackstar buzz-cut (which has been my own haircut of choice on and off for most of my life).

I discovered something very cruel: when your hair gets longer, the bald spots are more noticeable than ever. I more closely resembled Bobby Charlton than Major Tom.

Project cancelled.