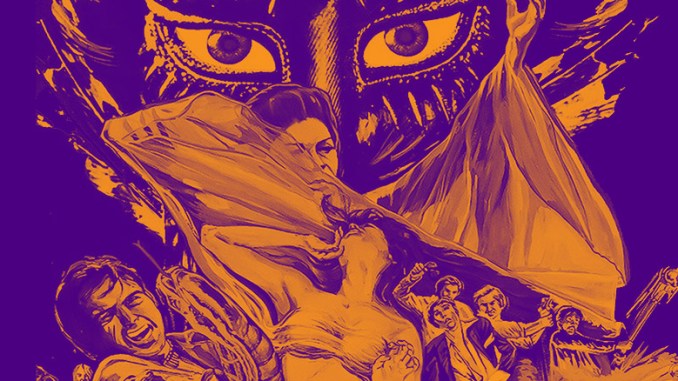

❉ An appreciation of Roddy McDowall’s hallucinatory, sensual Folk Horror.

‘McDowall’s film is undeniably an odd beast, but an intriguing one, and one which repays the viewer. The characters feel at times lovingly trapped in a little world of their own, an appealing step or two away from mundane Reality which is entirely fitting with the notion of the entrancing yet ensnaring lure of the world of the Fae.’

In the very late 1960s, a 16th-century Scots ballad rewritten some two centuries later by Robert Burns is recalled by a former child star – from Hollywood by way of London’s Herne Hill (an oddly fitting location, given the story that he chose to tell on celluloid) – and by now best known for portraying a super-intelligent simian. Enraptured by it, he does something that he’s never done before and never will again: he decides to direct a film version of the tale. In so doing, Roddy McDowall (for it is he) creates a very early example of a genre of Horror cinema that has risen to prominence in recent years.

Folk Horror – whether named by Mark Gatiss, Jonathan Rigby or whoever else you may care to suggest – really became a thing during the 2000s. It has become surprisingly influential (and divisive) ever since, rather oddly since its main established canon comprises three films: Witchfinder General, Blood On Satan’s Claw and The Wicker Man. The first two of these are set firmly in some semi-mythical 17th to 18th Century, and even the third has a certain ethos of another time and place, Summerisle feeling almost like some more sinister version of Brigadoon, cut off in its own odd, anachronistic bubble for all of its brand-label spirits and tinned vegetables. It’s surprisingly easy to imagine a full, period piece version of the tale: only minor cosmetic changes would be needed.

In more recent years, Ben Wheatley has shown that Folk Horror can flourish easily in any time, from A Field In England during the Civil War to somewhere, very much in the present, In The Earth. His realisation is that Folk Horror endures anywhere and anywhen, and it’s a very powerful bit of knowledge. But he wasn’t the first to understand.

McDowall took the song’s story of a beautiful young man who’s the lustful object of every female eye – much to his delight, until one of these women turns out to be the vengeful Faerie Queen herself – and wrenched it from 1500s Scotland very firmly into the present day of the end of the 1960s: and, in so doing, created a powerful, intriguing, and very individual period piece of its own.

The simple-yet-inspired notion of transplanting the tale to the cusp of the Swinging Sixties into the Glam Seventies gives rise to a suitably universal and timeless narrative, one that both bewitches and warns. At times, the finished product can feel surprisingly like some obscure feature-length Public Information Film, albeit one which cautions us against dangers rather less prosaic than frozen ponds and electricity sub-stations: a somewhat unexpected sensation.

And the viewer is further disorientated by the eclectic cast which McDowall gathered to people the roles. A Hollywood goddess with starring roles in everything from musicals and light comedies to heavyweight literary adaptations and Westerns: a venerable camp British character actor most familiar from comedies running the gamut of Ealing to Carry On, as well as co-starring with Eric Sykes and narrating the tales of that other well-known anthropomorphic bear, Mary Plain, for Jackanory; and a dazzling cast of younger talent, including the director-to-be of Withnail And I, Roger Moore’s Bond’s first bed partner, Frank–N–Furter’s Adonis of a creation Rocky Horror, the New Avenger who was to give the fashion world a whole new hairstyle, and even that formidable private eye and adventuress, Big Harriet Zapper. And, as the romantic leads, a Hammer heroine-in-waiting and a roguish chap who was set for later fame as an idiosyncratic antiques expert and a foul-mouthed Old West barman.

All of them playing their parts in giving an old story new, and startling, life.

Starting not in some romantic Scottish glen, but in a very contemporary London of imposing town houses and a convoy of beautiful vintage Jaguars and other expensive cars, our characters decamp rapidly via a similarly almost dreamlike and beautiful Newcastle to a massive country estate in the depths of Bonnie Scotland, our hero Tom Lynn (very clever, guys…) still very much the apple of his silver vixen of a lover Michaela ‘Micky’ Cazaret’s eye. It all seems decidedly bucolic and lotus-eating, but a sour note is struck as, prior to the journey, one of Micky’s most loyal acolytes, pleading and all but begging, is brusquely dismissed from her inner circle. The disquieting incident, however, is quickly and discreetly brushed under the carpet as the gathered flock of Bright Young Things and their glamorous, older benefactor look all set to embark on the hedonistic adventure of a lifetime. It’s Pentangle supplying the tunes rather than The Who or Jim Morrison, but we definitely feel that, at last, the Young Generation may have found their own secular Eden in which to play.

And, as their days pass in a whirl of drink, drugs, fornication, found puppies and general elegant lounging, that at first seems to be the case…but it soon becomes clear that Tom, true to the ballad, is proving irresistible to several of the girls, including Janet, the beautiful daughter of the local vicar, whose feelings for him run rather deeper than simple Lust, and are reciprocated…to the increasing displeasure of their majestic hostess. Speaking for her, her factotum Elroy confides in Tom that Micky grants her favours to men very selectively, and possessively…and that Tom’s predecessors, when they decided to stray, have tended to end up violently dead, ostensibly in car accidents…’You wouldn’t believe, would you, that a face could spread so wide?’, he observes with a cheerful leer, showing Tom photos of what was left of these unfortunate souls…

But, despite these warnings and those of Janet’s scholarly father, Tom does decide to stray – and Janet’s pregnancy following his dalliance with her only reinforces his determination to do the right thing. It’s a noble act, even an heroic one.

It’s also a very big mistake.

For Micky – and is she simply a well-preserved MILF type, or something altogether older, wiser, and deadlier? – is about to bring whole new levels of meaning to the old saw that Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned…

McDowall’s film is undeniably an odd beast, but an intriguing one, and one which repays the viewer. It may seem to some to be somewhat overlong, but I find that the lengthy stretches of film which do little but appraise the landscape and scenery to be more in the vein of poetic longueurs: The land lies at the roots of all Faerie, and all Folk Horror, and everything from vast, elegant manor houses to wide stretches of verdant moorland is photographed by Billy Williams in a manner that can be almost hypnotic, and fully suggestive of the land’s ability to be everything from seductive to sinister. The characters feel at times lovingly trapped in a little world of their own, an appealing step or two away from mundane Reality which is entirely fitting with the notion of the entrancing yet ensnaring lure of the world of the Fae. The ancient yet timeless songs and music on the soundtrack, courtesy of Pentangle, add further to this hallucinatory, sensual mixture.

But always lurking at the core of the tale is a narrative of symbiosis blended with conflict: the interaction of the Old, and the Young. Ava Gardner’s Micky and Richard Wattis’ Elroy are avatars of the former, both delighting in (and, maybe, feeding from) the enthusiasm and vitality of the latter: but that last group, as represented by the likes of Ian McShane’s Tom and Stephanie Beacham’s Janet, as well as Micky’s two youthful Covens, is also the source of jealousy and eventual rage among the Old, once they are again reminded of the harsh lesson that, while both may co-exist happily, neither can hope to last too long in the intimate company of each other. The then-topical and still relevant concern of the Generation Gap, as much as anything else, is writ large in this recounting of the story.

Is Micky truly the Queen of the Fae? McDowall and his scriptwriter William Spier play a very sly game here indeed. In the decade of extremely popular mysticism and all manner of new and wonderful psychotropic and hallucinogenic drugs, the boundaries between the Natural and the Supernatural become ever more blurred. Does Micky owe her good looks to cosmetic surgery and a good make-up man, or is she genuinely immortal and ageless? Is the spiked drink that she offers to Tom a simple chemical Mickey Finn, or something altogether more sorcerous? Does Tom genuinely transform into a hunted bear during his subsequent flight and pursuit, or is his drug-addled brain playing sensory tricks on him? The film, to its credit, never gives concrete answers. Everything is kept carefully ambiguous. However, such things as the end credits labelling of Micky’s two sets of Bright Young Things as Covens, and the final, chilling close-up of her beautiful, implacable eyes as Pentangle sing of the Faerie Queen, do suggest that what has transpired is more than the simple and prosaic.

‘I’ll swallow anything as long as it’s illegal!’, Madeline Smith chirps memorably during an early scene, and although it’s undeniably a fun line (and one guaranteed to appeal to the lustful everywhere), it’s also perhaps the key to understanding the film. Shift your line of sight just a fraction, and it can be interpreted justifiably as a relish and desire to eat the forbidden fruit, with all of the Edenic resonances of loss of Innocence and gaining of Knowledge which that implies. True, it’s Tom who really learns some unpleasant Truths, but he ultimately survives and finds True Love with Janet.

But the final word, and final, wild stare is left to the Queen of the Fae. Still out there, still looking for True Love herself, and still as merciless with those who, knowingly or otherwise, dare defy her and her power. Maybe that Public Information Film comparison isn’t so frivolous after all.

For the best rendition of the ballad itself, I urge you to seek out Fairport Convention’s delicately sinister version. However, if you want to see a fresh take on an old tale, and one which demonstrates admirably just how timeless such a tale can be, then watch, marvel at, and enjoy The Ballad Of Tam-Lin.

Let the song be forever heard.

❉ ‘The Ballad of Tam Lin’ (BFI Blu-ray) released on 10 October 2022, RRP: £19.99 / Cat. no. BFIB1454 / Cert 15. Order from the BFI Shop: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/the-ballad-of-tam-lin-blu-ray.html.

❉ Ken Shinn is a lifelong fan of all things cult and is a regular contributor to We Are Cult. His 58 years have seen him contribute to works overseen by the likes of TV Cream and the British Horror Films Group, as well as a whole batch of short stories of the fantastic, with his first novel on the way. Whatever the field, he intends to enjoy Cult in all its forms for many years to come.