❉ Glen McCulla waxes lyrical on master of illusion Georges Méliès and the origins of cinema.

“Film is fantasy made reel”, as film critic Alan Frank so elegently and eloquently phrased it, and in the hallowed halls of the history of cinema there is one man who stands as a true pioneer in the field of filmic wizardry – artist, alchemist, magician, special effects pioneer and lord of illusions Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès.

The scion of a successful and respectable family of shoemakers, Méliès had already shown an artistic bent as a youth by drawing caricatures of schoolmates and sketching elaborate fantastical landscapes and ‘castles in the air’ in his scholarly exercise books before working briefly alongside his brothers at the family factory sewing boots.

The future course of both his life and the entertainment industry would change in 1994 when he was sent by his father from Paris to London in order to improve his English whilst working as a clerk for an acquaintance. While living and working as a stranger in a strange land the young man would chance upon the famed ‘Home of Mystery’, Piccadilly’s Egyptian Hall, the Sphinx and heiroglyphic-bedecked exhibition hall managed by William Morton and featuring the performances of his protoges: the spiritualism-debunking illusionists John Nevil Maskelyn and George Cooke, inventors of the stage trick of levitation (Maskelyne would continue his career in magic after Cooke’s departure from this world alongside David Devant [with or without his Spirit Wife]).

Inspired and enraptured by the art of illusion and stage magic, Méliès would return home to the factory on the Boulevard Saint-Martin with a mind aflame with the endless possibilities presented by the spectacle of sleight of hand and sorcery and became a regular visitor to the Theatre Robert-Houdin at 8 Boulevard des Italiens – the Parisian home of magic established by the famed Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. In 1888, using the money from selling his share of their retiring father’s business to his brothers, Méliès purchased the theatre from Robert-Houdin’s daughter-in-law and would go to renovate and update the aging establishment’s array of trap doors, levers and pulleys before making it the home of his own developing act (which he had honed at the Grevin Wax Museum’s cabinet fantastique – a chamber of the waxworks reserved for magic shows) and create and refine a number of innovative tricks and illusions over the next few years.

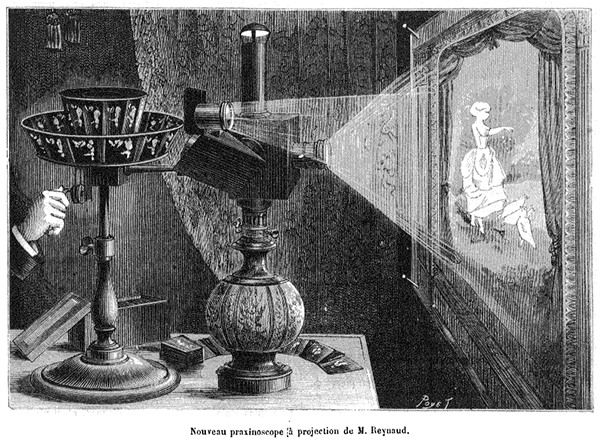

By this time already an established master of magic beneath the proscenium arch, Méliès would attend a demonstration on the 28th December 1895 in the Indian Salon of the Grand Cafe on the Boulevard des Capucines by the Lumiere brothers of their brand new cinematographe – a method of projecting motion pictures for an audience as opposed to Thomas Edison’s contemporaneous early one-person ‘peep show’ kinetoscope.

This exhibition in the basement rooms of the Parisian Grand Cafe would prove – to bring a musical allusion to the reals of filmic illusion – very much the 4th June 1976 Sex Pistols at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall of its day. Méliès watched as Auguste and Louis Lumiere showed a series of ten short films (each consisting of approximately 17 metres of 35 mm film and running between 40 and 50 seconds), mostly actualites or very short documentary films such as Les Forgerons (The Blacksmiths) showing a brief snippet of work at a blacksmith’s anvil and Le Debarquement du Congres de Photographie a Lyon quite literally doing what it says on the tin – or film can – by showing the arrival by boat of the Photographical Congress, but also containing the very first narrative film (and also the very first motion picture in the genre of comedy) L’ Arroseur Arrose (also known as The Gardener or The Sprinkler Sprinkled) in which a gardener watering his plants with a hose is baffled when a young boy stands on his hose and stops the flow of water only to remove the blockage as the protagonist looks into the hose’s nozzle and release a jet of water into his face.

Like the nascent members of The Fall, The Smiths and Joy Division at the Lesser Free Trade Hall eighty-one years later, Méliès would be inspired by the crude but trailblazing showcase before him and resolve to seize this new art form himself and add his own unique and individual quirks and talents to transform it into something new, protean and powerful. When, seized by this suddent creative spark of inspiration, Méliès attempted to purchase the cinematographe from les freres Lumieres the brothers demurred.

Melies would soon find himself purchasing his first movie projector in London from fellow future film pioneer Robert W. Paul (who would produce early trick effect flicks such as the 1901 The Haunted Curiosity Shop – a phantasmogoria of effects that would include the very first reanimated Egyptian mummy seen on the silver screen), a strange collaboration akin to Peter Hook buying his first bass guitar from Mark E. Smith. Though, as Paul had custom-built his own projection system after obtaining an early unpatented Edison Kinetoscope and stripping it down and adapting it as an English version, perhaps he was more like an early Dawn of Cinema Brian May building his guitar from his father’s coffee table. These ’70s rock metaphors may be getting a little tortuous now.

Converting the projector into a camera (dubbed ‘The Machine Gun’ because of its noisiness) and buying a few rolls of Eastman Kodak film, Méliès returned from London to Paris where a cinematic miracle would soon occur. Filming a simple Parisian street scene (akin to the Lumieres’ straightforward documents of the whirl and the rush of humanity) in the Place de l’Opera, his jerry-built camera suddenly jammed as a bus passed by. By the time that Méliès unstuck and restarted the mechanism, the bus had moved on and a hearse had taken its place. Much to his suprise and delight, when he projected the day’s footage he saw a bus suddenly transform into a hearse before his very eyes. The simple effect of the jump-cut had been serendipitously discovered, the first real special effect wherein anything could turn into anything – or even vanish into thin air.

Man had become magician: now anything at all could be called upon to happen. Méliès could combine his knowledge of theatrical prestidigitation with cinematic technique and become the lord of illusion. The future was fantasy. The future was film.

❉ Glen McCulla has had a lifetime-long interest in film, history and film history – especially the genres of science fiction, fantasy and horror. He sometimes airs his maunderings on his blog at http://psychtronickinematograph.blogspot.co.uk/ and skulks moodily on Twitter at @ColdLazarou