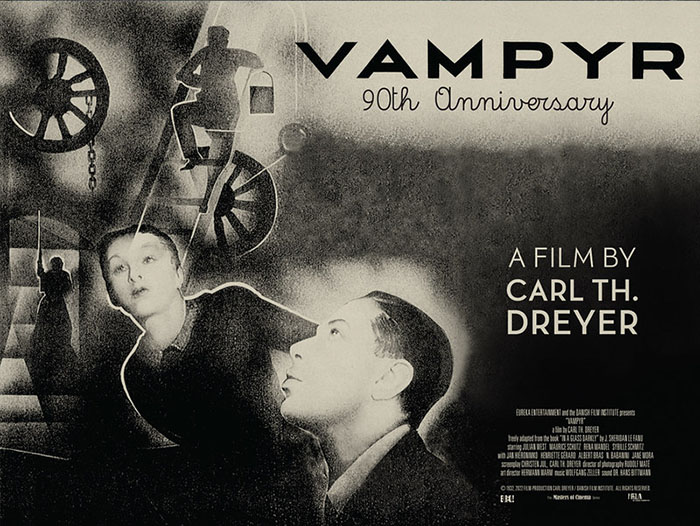

❉ An appreciation of Carl Th. Dreyer’s beautiful, strange and unsettling film, recently restored by Eureka for its 90th anniversary.

“There’s an argument to be made that Vampyr is the first dreamlike horror film to go for a sense of realism… The film’s most notorious centrepiece involves our hero feeling powerless in the face of death, and powerlessness seems to be the abiding dramatic choice throughout. It’s a film of passive performances, of people who are subject to the wild vagaries of fate and evil.”

So, first things first, I actually bought a Blu-ray player especially so I could see this film. Once our valiant head editor of We Are Cult (the Cultivator maybe?) dangled the possibility of me being able to review this film there was no doubt in my mind that I had to break in a machine with this weird little masterpiece. Because I am very much of the belief that once you’ve seen Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931) it’s a film that you will immediately become a bit obsessed with.

Anyway. Every now and then a celebrated film director from the more cerebral, arty side of the medium decides to try and do a horror film. Off the top of my head there’s Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf, Powell’s Peeping Tom, Herzog’s Nosferatu remake, Von Trier’s House That Jack Built, arguably Scorsese’s Shutter Island and many more. It probably stems from Hitchcock’s seemingly effortless ability to leap from genre film to genre film whilst still maintaining artistic integrity, the sort of integrity other directors long to replicate but frequently struggle with. But my tip for the first real art film/horror hybrid is Vampyr.

Dreyer had been a director whose reputation was pretty much built on his ability to combine realism and expressionism, and whose success had culminated in the critically lauded – but wildly unsuccessful commercially – The Passion of Joan of Arc of 1928. Faced with the collapse of the Danish film industry, a nationwide struggle for cinema to come to terms with sound film and something of a reputation for making critically lauded but mostly commercially unsuccessful films, Dreyer decided to make a big commercial genre film. And I think it’s pretty much safe to say that the only real way Vampyr fails is as a big shiny commercial hit. It’s a beautiful, strange and unsettling film but as far from a commercial hit as you can get.

In fact, in one of the very strong documentaries on this disc as extras, film historian, genre expert and unusual facial hair aficionado Kim Newman goes out of his way to describe how Vampyr was made contemporaneously with Tod Browning’s Dracula also of 1931. They’re both adaptations, although Browning’s film is far closer to Stoker’s novel than Vampyr is to the works of Sheridan Le Fanu. Dreyer seems to have cherry picked themes, motifs and images from these stories – and ironically taken nothing from Camilla which is still the most adapted non-Stoker vampire story in the canon. It’s an approach that works really well here. There are similarities between the two sisters here and the usual Mina/ Lucy relationship. And crucially they both build on the innovations of expressionist cinema, but if anything Vampyr has more in common with George Melford’s Spanish language Dracula filmed on the set of the more famous Lugosi film during the night shifts.

Although Vampyr’s hero Allan Gray ostensibly owes something to the usual Jonathan Harker audience identification figure, he’s really a much stranger figure. Played by Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, French born socialite and editor, who gave Dreyer the money for the film on the basis that he would play the lead role (under the name of Julian West), he’s not in any way a born actor but is perfect for the strange, dreamlike tone of Dreyer’s film. As audience identification figures go, Gray is strangely blank faced (or at best in a state of mild alarm and panic), so it makes us as viewers feel a little adrift in this weird fictional world. The most notorious scene of the film is framed around a combination of Gray’s powerless panic and his powerless blankness, and honestly few actors could have done as good a job. He feels off throughout. There’s also a weird accidental visual likeness to Lovecraft which makes Gray’s role as occult obsessed dilettante have an extra unintended frisson.

Gunzburg was not alone as being an amateur. In fact, there’s barely any trained actors in the film at all. Dreyer was far more interested in embracing the look of an actor over their acting ability. Thusly our villains, the Village Doctor and Marguerite Chopin, our titular vampire, look absolutely amazing, and feel like figures from early photography rather than stage villains. I’d go as far as saying Henriette Gerard as Chopin is one of the all-time great horror villains, a troubling and deeply unemotional and somewhat androgynous figure of malevolence and strange disquiet. She genuinely feels like someone who would worry the edges of your dreams, a sort of malignant present rather than a typical villain.

There’s an argument to be made that Vampyr is the first dreamlike horror film to go for a sense of realism. God knows the German expressionists were all for creating dreamlike evocations of nightmares and dreamscapes, but there’s something defiantly theatrical about the sets and performances in Dr Caligari or the films of Lon Chaney that Dreyer is determined to resist. The roles of much of the film are very much from that world – the mad doctor, the doomed nobleman, the sisters, our bemused young hero – but act almost as if they’re reacting against the events of the film. The film’s most notorious centrepiece involves our hero feeling powerless in the face of death, and powerlessness seems to be the abiding dramatic choice throughout. It’s a film of passive performances, of people who are subject to the wild vagaries of fate and evil.

Dreyer achieves much of this dreamlike tone by shooting his amateurs entirely on location. Even the strangest buildings here were very real. And by having his non actors moving around these spaces there’s a sort of weird tension that Dreyer achieves. The film seems fascinated by contradictions: waking dreams; the walking dead; a recurring motif of shadows that appear to not to actually belong to anything. Kim Newman in his essay mentions Herzog as another director who played with these sorts of ideas, especially in his films with Bruno S and his infamous use of a hypnotised cast in Heart of Glass. It’s a film that is determined to evade a simple reading. There’s a sort of dream logic at play even before the film decides to literally apply itself to following the logic of dreams during the film’s most notorious sequence where our hero sees himself being interred in a coffin by the villains – both from above as a spectre and inside as the corpse itself watching the nails coming in.

The film, even in this beautiful restoration, seems to almost shimmer. Kim Newman describes it as having a “horror of whiteness” (literally so in the end scenes in the flour mill). Visually it reminds you very much of the photography of Man Ray, and there’s a definite influence of surrealism and dada in the film. Dreyer was living in Paris during the period he was making the movie and was very much involved in the city’s art scene, so this is almost certainly no accident. There’s also something of the early films of Luis Bunuel (what is L’Age D’Or if not an existential, nightmare black horror comedy?). Certainly the film prepares the way visually for the works of Jean Cocteau who seems to take Dreyer’s ideas and take them to their ultimate, dreamlike end. There’s also something that predicts the tone of Pere Portabella’s unique Cuadecuc, Vampir from 1970 which was shot using behind the scenes footage from the Jesus Franco film Count Dracula (also of 1970).

Dreyer isn’t really interested in telling a direct story here, which is why he probably chose to cherry pick elements of Le Fanu’s writing, but instead evoking a sort of sustained feeling of unease. The screenplay is so slight it’s almost absurd – try describing it to someone and you’ll struggle very quickly. Narrative coincidences here feel more like the repeated motifs you get surfacing in dreams. For a sound film it’s almost silent, but also one that uses that silence brilliantly. There are so many arguments to be had about how sound put back the progress of film as an artistic medium, but Dreyer seems to accurately know when to use sound to use it sparingly.

There’s another filmmaker that this film reminds me of, and that’s David Lynch. The whole end of the film was rewritten because Dreyer had visual inspiration from a nearby mill and junked the cliched swamp for the more troubling death-by-flour we actually get. There’s a preoccupation with where dreams end and, to coin a phrase, “who is the dreamer who dreams”, and an embrace of visual non sequiturs. And the final haunting of the Village Doctor by the spectre of dead Lord is one of those strange artistic choices (a huge fading in and out static image of his head) that feels like a director who’s less interested in the conventional language of cinema and instead articulating a very vivid, unique image within their own mind which anyone who has seen the Twin Peaks revival will know all too well.

Honestly, Vampyr is a very difficult film to write about because it is very literally less a narrative and more an experience you end up drifting through. It’s a tone poem – and as I’m getting all pretentious, I may as well go the whole hog and say it’s sort of the visual equivalent of similarly dada/surrealist adjacent Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes, the far more loosely structured and freeform counterparts to his more melodic and traditional Gymnopedies. It’s a film that’s hard to adequately do justice to because it’s so nebulous and dreamlike. It’s a film to experience, but also one that feels very much like the end of a dream you half forget upon waking.

❉ VAMPYR (1932) Limited Edition Blu-ray was released 30 May 2022 on Blu-ray as a part of The Masters of Cinema Series. Available to order from the Eureka Store: https://eurekavideo.co.uk/movie/vampyr-limited-edition-box-set-3000-copies/

❉ Chris Browning is a librarian but writes and draws comics and other strange things to keep himself out of trouble: he can be found on Twitter as @commonswings but be warned he does spend a lot of time posting photos of his cats.