❉ Take a trip down some of the lesser-known, uncharted byways of sixties British cinema.

We live in a golden era of cinematic reappraisal. Rare films are released regularly through DVD labels like BFI Flipside, Network and Renown, while the archive TV channel Talking Pictures TV is constantly screening a plethora of B movies and lost films of classic British cinema. Almost gone are the days when unreleased films were procured in the form of badly ripped DVD copies from questionable purveyors on internet forums (It isn’t just me, right? Right?). So, while most of the films reviewed here are available, the few that aren’t may become so and where possible, links are provided for anyone wishing to source the films discussed in this post. Talking Pictures TV (available on Freeview channel 81) has also screened quite a few of these titles and may offer repeat broadcasts in coming months.

❉ The Party’s Over (Guy Hamilton, 1965)

If Performance (Nicolas Roeg, 1970) represented the comedown at the end of the 1960s, The Party’s Over represents the comedown from the early part of the decade. Fittingly, the film begins with a hangover. The protagonists are eerily silent as they wander home after a night out, their body language conveying an eerie coldness and a complete lack of camaraderie which is later reinforced by individual instances of amorality and borderline sociopathic behaviour.

The Party’s Over follows the story of Melina, the daughter of a rich American industrialist, as she falls in with a group of beatniks in London. Melina’s fiancé is despatched from the States to find her, but with the help of her friends she eludes him, dreading a return to her former life. Oliver Reed is in love with Melina and guards her jealously, even though his affections are not reciprocated. Amid a wild party and much drunken confusion, Melina vanishes, and it is left to the fiancé to reconstruct the events of the evening which led to her disappearance.

The censor was famously upset over an instance of ‘implied necrophilia’ in one scene of the film where the party revellers strip Melina’s corpse, thinking that she is simply unconscious, not dead (but implicit is the idea that her lover goes a little further than that). This earned it three requested re-cuts by the censor, which meant that though it was completed in 1963, the film wasn’t released until 1965. Changes requested included a voice-over by Oliver Reed and a different, happier ending. Director Guy Hamilton removed his name from the credits in protest.

The film offers an unflattering and probably wildly inaccurate account of beatnik culture in London, but for all that it functions as a social document as well as a compelling mystery-told-in-flashback. Also, Oliver Reed brought an intense charisma to low-budget British cinema in the early 1960s (see Joseph Losey’s dystopian science fiction film The Damned), and The Party’s Over is no exception. The film is worth a watch for Reed’s performance alone.

❉ The Party’s Over is available on DVD from BFI Flipside.

❉ The Little Ones (Jim O’Connolly, 1965)

The Little Ones might be a charming number from the Children’s Film Foundation of the type that were shown at Saturday cinema matinees were it not for the film’s underlying themes of racial tension which subtly escalate to an emotionally charged ending.

Ted’s parents are racists who beat him regularly and tell him to keep away from Jackie, who is the son of a prostitute. Jackie’s mum is harmless enough, but his Jamaican father left her years ago, which leads Jackie to muse on his father’s life and travels, and his astonishment that anyone would ever leave the sun-bleached shores of Jamaica for London. Stowing away in a furniture removal van bound for Liverpool, the boys decide to catch the next ship leaving from the Liverpool docks for Jamaica because it can’t possibly be worse than England…

When the boys go on a petty crime spree to obtain food for their journey they are painstakingly pursued and finally collared by a local policeman who sits them down and gives them a good talking to. The policeman loses his temper with Jackie and blurts out ‘don’t talk to me like that you little n…’. He pauses before he can complete the sentence, shocked at his own intolerance. His apparent self-image as a progressive liberal is deflated in one unguarded moment and though he sheepishly apologises to Jackie, the damage has been done. It’s a powerful moment which instantly elevates the film into something with a socially critical edge.

Originally titled ‘The Fledgelings’, The Little Ones was a second feature (or ‘B’ movie), distributed by Columbia pictures. Like most one-hour second features from the early 60s it was made on a minuscule budget of £20,000 (the average budget for even a cheap British feature film was in the region of £150,000) and sank without a trace following its release. Bizarrely, the New York Times was one of the few outlets to review the film, calling it ‘a vest-pocket joy from Britain that quietly crept into town yesterday on a circuit double-bill. At the bottom, naturally. We have one objection. This low-budget entry, made by some people we never heard of and running for only an hour, should run about twice as long.’

Which is a shame, because The Little Ones deserves reappraisal not just because it’s a genuinely charming picture but because it explores aspects of British life which are seldom tackled head-on in national cinema. Shot in black and white in handheld realist style, the film was released just as London was on the cusp of ‘Swinging’, but aesthetically the film couldn’t be further away from beehive hairdos and the Mersey Sound. Cinematically, its partner is the short film Jemima + Johnny, which has received far more academic and critical attention.

❉ The Little Ones is, sadly, only available to view on the computer terminals at the BFI Reuben Library.

❉ Otley (Dick Clement, 1968)

Dick Clement’s directorial debut Otley follows the life and crimes of Gerald Arthur Otley, a petty criminal and perpetual ne’er-do-well who unwittingly finds himself embroiled in the British Intelligence network.

It’s unsurprising that in the era of the satire boom the increasingly popular spy genre should give birth to its own filmic parodies (Our Man Flint, Casino Royale, Carry on Spying, to name a few). Otley belongs to that cycle, though I’d argue that it provides a more subtle and well-observed lampoon of the sixties spy film. The film is set at the height of Swinging London and features Tom Courtenay (who made his mark as a serial fantasist in Billy Liar) as Otley, a hapless antiques dealer and small-time crook who winds up inadvertently caught in a net of intrigue. Tom Courtenay convinces as the cowardly, put-upon lead, while Leonard Rossiter is brilliant as the rogue operator who trains Otley to be an agent, only to set him up for a fall.

The film is far from an out-and-out burlesque. Rather, Gerald Otley’s travails allow for Clement to gently poke fun at the convoluted nature of government agencies, at free love, hippies and the British class system, while eventually returning to the status quo as Gerald is relieved of his duty and free to return to his old life. In the tradition of Swinging London films, in the final scene he refers to the entire sequence of events as a ‘fantasy’.

Given Courtenay’s profile as well as the fact that the film is a light-hearted take on a very popular genre, it’s hard to see why it remains practically unknown.

❉ Otley is available to purchase on DVD.

❉ Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (Cyril Frankel, 1960)

The low-budget end of the British cinema spectrum allowed for exploration of the most lurid themes, but also the most hard-hitting and controversial. That’s how Hammer branded their 1960 film Never Take Sweets From a Stranger (American title Never Take Candy from a Stranger) a crime thriller set in small-town Canada which follows the trial of a respected member of society who is accused of molesting a young girl.

It goes without saying that this is a film which is terrifically uncomfortable to watch. It’s true that themes of child abduction and sexual assault abound in crime thrillers and horror films of the era like Pat Jackson’s Don’t Talk to Strange Men (1962) and Michael Carreras’ Maniac (1963). But while sensationalism is a firm part of Never Take Sweets (‘this story takes place in eastern Canada, but it could happen to any child, anywhere’ says the trailer voiceover) unlike the previously cited titles, the film actually handles its subject with surprising empathy and sensitivity.

In the midst of an emotionally harrowing trial in which the Carter family are ostracised from society by dint of the audacity of their accusations, the 9 year old plaintiff takes the stand. The film’s commentary is less about the lurid predatory premise and more about the difficulties of holding respected members of society to account in spite of rigid social hierarchies – a theme which seems especially relevant for modern audiences inhabiting a post-Yewtree world. The Carters have just moved to the town and are not known or loved in the community. The defendant, Clarence Olderberry Sr, is a member of the wealthiest, most highly regarded family in town, and his power and influence are such that he is acquitted by the jury despite the evidence. Emboldened by this verdict, he prepares to strike again.

The tension is built up masterfully in the final scene as Olderberry pursues two terrified young girls through the woods. He is a mute spectre, silently stalking through the forest -an irredeemable monster comprised of uncontrolled impulses and a complete lack of remorse. The horror is chilling, and very immediate.

This is a well-written, superbly acted thriller which evokes tension beautifully with its soundtrack and narrative.

❉ Never Take Sweets From a Stranger is available to buy as part of Hammer’s Icons of Suspense Collection.

❉ The Rolling Stones’ Rock N Roll Circus

“You’ve heard of Oxford Circus! You’ve heard of Piccadilly Circus! Well this is the Rolling Stones Rock N Roll Circus, and we’ve got sights and sounds and marvels to delight your eyes and ears!” – Mick Jagger introduces the show.

In 1968 Mick Jagger asked the best of the sixties music scene to dress up as circus folk and get together in a cramped television studio to film a series of performances over 48 hours. While the rationale for staging this event under the dressing of a ‘circus’ performance (with Jagger as ringleader) is unclear, The Who, Jethro Tull, Marianne Faithful, John Lennon (the list goes on and on) duly complied, resulting in a cultural oddity which includes some fantastic footage. Here’s John Lennon and Mick Jagger sharing awkward banter while discussing Dirty Mac, the one-off super-group that Lennon put together specifically for the show:

Music journalist David Dalton, who was sitting in the studio audience, captured the bizarre energy of the event:

It was hard to believe it was actually happening. Lennon, Keith Richards, Clapton and Mitch Mitchell playing together in a Supergroup, a real circus with tigers, plate spinners, a boxing kangaroo, the Stones, the Who, acrobats, clowns, midgets and a fire eater, and entirely planned and produced by the Stones themselves.

But until its television broadcast in 1996, The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus was truly a lost film – or at least an unseen one. The reason why the film wasn’t released at the time are unclear, but in his sleeve notes for the CD release Dalton suggests that it boiled down to simple vanity: Jagger was unhappy with his performance, and with how he appeared on camera.

❉ The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus is available to purchase through Amazon on either DVD or CD format.

❉ The Committee (Peter Sykes, 1968)

Last but definitely weirdest is Peter Sykes’ The Committee, an exceptionally strange film from a young new talent who was making a name for himself in the mid-60s, mainly on the experimental end of the cinema spectrum.

The Committee is a surreal film which focuses on themes of individual responsibility, the individual’s role in society and his/her relationship with the establishment. The unnamed protagonist, played by Paul Jones, is walking through the woods when he is offered a ride by a mild-mannered, buttoned-down, middle-class gentleman. Jones becomes so irate with his driver’s banal conversation that he chops off his head and, realising that he has made something of a faux pas, sews it back on again. The gentleman wakes up and continues on as though nothing has happened.

A few years later Jones is asked to take part in the Committee of the film’s title – a convention of sorts in which young people are invited to gather to discuss an unspecified issue. We are told that Committees are what make society run smoothly, although no one is really clear on what their function might be. Jones worries that the Committee has been called because of him.

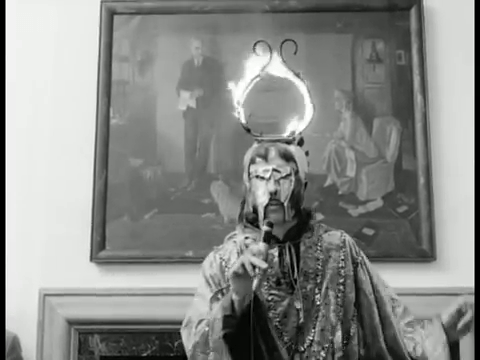

Sykes’ directorial debut has a number of notable features, not least of which is a soundtrack by Pink Floyd, who at this point were only just teetering on the verge of becoming ‘known’. But the pièce de résistance has to be a surprise gig mid-film by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, performing their hit single ‘Fire’.

Following The Committee Sykes was offered the chance to make a high budget film titled The Rules of War but opted instead to direct Venom (1971), a romantic horror film which offered a better opportunity to be ‘creative.’ Sykes wasn’t the only young director realising his potential in horror; by the late 1960s the horror genre had attracted a number of young directors who perceived some room for innovation (however limited) working for companies like Hammer, including Stephen Weeks, (I, Monster), Peter Sasdy (Taste the Blood of Dracula) and Gordon Hessler (Cry of the Banshee, Scream and Scream Again).

❉ Privilege (Peter Watkins, 1967)

The Committee appears to have a lot in common with Peter Watkins’ Privilege (1967), a film set in a dystopian futuristic Britain in which Paul Jones plays idolised pop megastar Steven Shorter. ‘It’ girl Jean Shrimpton plays his lover and confidant. Like other Watkins offerings (Culloden, 1964) the film takes the form of a fictionalised documentary, and is voiced by a dispassionate narrator who charts Steven Shorter’s mental breakdown as his public image as a deified celebrity and role-model crushes his own precarious sense-of-self.

❉ The Committee is available in full on Youtube, while Privilege is a little better-known and can be found through BFI Flipside.

❉ A version of this post originally appeared on 60s British Cinema.

❉ Check out 1960s British Cinema Project on WordPress, Facebook and Twitter.

❉ Follow Laura Mayne on Twitter.