❉ Exploring the Star Trek creator’s attempts to get a new show on the air in the 70s.

What exactly was Gene Roddenberry – the ‘Great Bird of the Galaxy’ – doing in the period between the third of June 1969 when Turnabout Intruder, the final episode of the third and final season of Star Trek, was broadcast and its rebirth in the form of the 6 December 1979 premiere of Star Trek: the Motion Picture catapulting Captain Kirk and co onto the silver screen? What can we see in the dark backward and abysm of time, this lacuna coil ‘twixt television death and cinematic resurrection?

Roddenberry had, of course, already relinquished full control and oversight of his Wagon Train to the stars child after its second season – handing over the producing reigns to the much-maligned Fed Freiberger for season three. But one wonders what happened between Trek‘s death slot tumble into final cancellation and William Shatner’s (probably apocryphal, but “When forced choose between the truth and the legend, print the legend” and all that) story of wandering through the seemingly empty Paramount backlot while on a break from filming the Western series Barbary Coast – you may also recognise his co-star Doug McClure from such things as this – in the mid-1970s:

“I had not, for the longest time, revisited the stage area where [we had] filmed. So one day I decided to go there, [and] as I’d been walking and remembering the times, I suddenly heard the sound of a typewriter! That was the strangest thing, ’cause these offices were deserted. So I followed the sound, till I came to the entrance of this building. I went down a hallway, where the offices of Star Trek were… I opened the door and there was Gene Roddenberry! He was sitting in a corner typing. I hadn’t seen him for five years. I said, ‘Gene – the series has been canceled.’ He said, ‘I know, I know the series has been canceled. I’m writing the movie!'”

Roddenberry, of course, had been busy at his trusty typewriter all this time – just writing other things than Star Trek, many of which would at last reach the stage of a filmed pilot movie before failing to blast off into a full series (most of which would stumble at the pilot hurdle, quite honestly). One of the ideas to which Roddenberry would return a number of times was the concept of the character Dylan Hunt – a 20th century man who finds himself stranded in a post-nuclear holocaust future after the devastating effects of a Third World War. The first attempt at the concept, Genesis II, was picked up for development by the CBS network and aired on the 23rd March 1973.

Directed by veteran John Llewellyn Moxey, who had made his featute film debut with the eerily Lovecraftian City of the Dead (released in the US as Horror Hotel, 1960) before going on to be a mainstay of American television series and TV movies, Genesis II relays to us the story of Hunt (“My name is Dylan Hunt. My story begins the day on which I died”) whom we meet very much in media res in a pre-title sequence as he he is led into what looks like a bank vault built inside an underground cavern. Deep inside New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns in the then future year of 1979 (the year I was born; it’s nice to feel futuristic and space age) the Ganymede project has been developing a prototype form of suspended animation in order to enable mankind to send astronauts further out into the vast reaches of space. The moustachioed Hunt (Alex Cord, who would become better known a decade later as Archangel in ’80s helicopter action wank Airwolf) is placed in the subterranean Xenon vault as a human test subject and sent into the arms of Morpheus, god of stasis booths, unaware that there is a fault in the caverns that soon causes an earthquake and buries the slumbering Hunt and the entire project beneath rubble.

And… credits! It’s certainly an attention-grabbing start.

By the time Dylan Van Winkle is roused from his little nap (for as anyone who’s ever read or watched Dune surely knows, the sleeper must awaken) he finds that he’s slept too long and finds himself a man out of time like Buck Rogers before him, in the distant space year of 2133. Discovered by the citizens of the post-nuclear holocaust socity of Pax led by Primus Kimbridge (Percy Rodriguez – a Roddenberry veteran, having played Commodore Stone of Starbase 11 in the Star Trek episode ‘Court Martial’ ), Hunt begs to be injected with the stimulant drugs that will aid his recovery only to be told that the future society possesses no such stuff. Thankfully, he is administered to by Lyra-a (Mariette Hartley, another Trek alumnus as Spock’s Zarabeth in ‘All Our Yesterdays’ and future Best Actress Emmy winner for the ‘Married’ instalment of The Incredible Hulk) and discovers that the hormones associated with sexual attraction have much the same recuperative effect. Like Uther Pendragon in John Boorman’s Excalibur, his lust holds him up.

Lyra-a confides to the convalescant Hunt that Pax is not all that it might seem – that for all their professed peace and harmony they were the party who started the Great Conflict that ravaged the Earth while Dylan dozed. She is a Tyrenian, one of the newer mutant strains of humanity to have evolved since the atomic horror, with twin hearts and superior strength and endurance to Mankind 1.0 as well as the distinguishing feature of two belly buttons – one above the other (Roddenberry’s revenge for the costume department having to cover the actresses’ navels on the original run of Trek). As the Paxian high council debate amongst themselves as to what is to be done about “the man from the past”, Lyra-a continues to persuade Hunt to be suspicious of his ‘captors’ until at night she smuggles Hunt to a sub-shuttle (an underground bullet train traversing a network of tunnels spanning beneath the whole globe) to whisk him away to her own city of Tyrenia.

After seeing more of the outer world, however, Hunt begins to realise that Lyra-a is filled with deceit down to her fetching redundant navel: the ordinary surviving populace exists under the domination of the mutant elite from their fortified city. Quickly wearying of being waited on by the Tyrenians’ subserviant human slaves whilst the city’s rulers use Lyra-a toconvince him to lend them his knowledge of nuclear physics to aid them, Dylan slips out of the city into the night to be amidst the whirl and rush of what remains of humanity and encounters the hulking Isiah (Ted Cassidy, The Addams Family‘s looming Lurch and another ex-Trek guest star having played the android Ruk in What Are Little Girls Made Of?), agent of Pax. Isiah and his fellow Paxians are planning a slave revolt against the Tyrenians which Hunt eagerly joins, sabotaging the nuclear weapon systems they are attempting to repair in order to gain final dominance over mere humans and returns to Pax – where he cannot help but rail against that society having grown peaceful and pacifistic to the point of indolence yet ruefully agrees to join with them as the lesser of two evils in their vow not to let a Great Conflict ever again occur.

Genesis II aired on CBS on 23 March, 1973, and even though Roddenberry had mapped out story outlines for a potential 20 episode season (including ‘Robot’s Return’, the seed of the idea that would percolate as In Thy Image, the mooted pilot for a Star Trek II sequel series later in the decade before eventually germinating as 1979’s Robert Wise-helmed Star Trek: the Motion Picture) the network turned down the series in favour of the also swiftly-cancelled at 14 episodes Planet of the Apes television series.

Putting his sketches for a Dylan Hunt, man of tomorrow series on the back burner, Roddenberry took a second idea to NBC – one which had been percolating in his mind since the final episode of the second season of Star Trek. ‘Assignment Earth’ had been conceived as a “backdoor pilot” for a potential spin-off series of the same name, a show concerning a mysterious not quite human being named Gary Seven (played by Robert Lansing) and his human companion on their adventures protecting mankind from threats both internal and extraterrestrial. While Roddenberry and Art Wallace’s co-authored screenplay had not resulted in a series of its own (Trek instead being recommissioned for a third season at the eleventh hour), the concept seemed one well worth exploring.

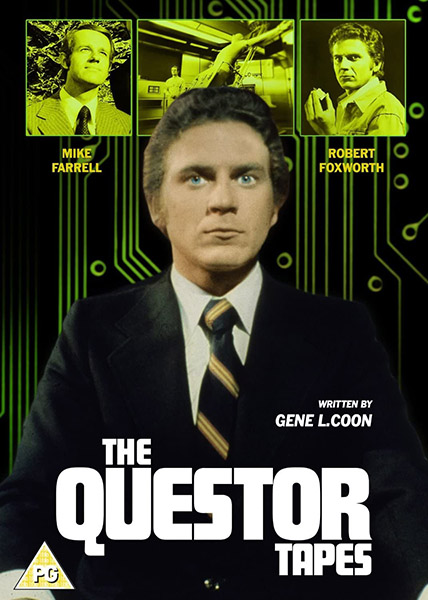

The Questor Tapes – also known under such alternative titles as Timerunners and Ein Computer wird gejagt (A Computer is Being Hunted) – was presented to the network yet again along with script treatments for a further season of 13 episodes, but this time NBC agreed to the commission. Involving the lead character of an android exploring what it means to be human, prefiguring Data from Star Trek: the Next Generation by some thirteen years, the lead part of the eponymous Questor was first offered to Mr Spock himself Leonard Nimoy who initially agreed and even posed for publicity photos before being replaced – possibly due to Nimoy and Roddenberry’s contemporaneous contretemps over royalties and likeness fees – by Robert Foxworth.

Working on the top secret Project Questor, a group of scientists including Dr Bradley (Majel Barrett again, Mrs Roddenberry making her customary guest appearance), Dr Chen (James Shigeta) and Dr Jerry Robinson (Mike Farrell, soon to become B.J. Hunnicutt of M*A*S*H fame) have been assembled by project leader Geoffrey Darro (Canadian character actor John Vernon, he of the gravelly voice and Dean Wormer of Animal House fame) to work individually on the component parts of a revolutionary human-like robot, completing the project begun years earlier by the mysteriously absent and presumed dead Professor Emil Vaslovik. When the finally assembled android – its half-formed features resembling the incipient form of Data’s daughter Lal from the TNG instalment ‘The Offspring’ – fails to activate correctly when programmed with the university data tapes, Robinson demands that Vaslovik’s bequested Questor tapes be used, much to Darro’s chagrin. When even this seems to fail, the personnel leave the laboratory for the night dejected, only for the robot to twitch into life, Frankenstein-style.

Having already played the Promethan creator Dr Victor Frankenstein himself the previous year in the ABC Wide World of Mystery adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel, Robert Foxworth here gives quite a good rendition of the newly-born creature quickly learning to function, walk, talk, read and speak. Quickly adapting his physiognomy to a more human appearance, Questor leaves the lab and seeks out Robinson – the sole human whom he has been instructed to trust through Vaslovik’s coding, and asks him to help him seek out his creator.

Leaving Los Angles and heading to London (portrayed with all the elan that the Universal backlot can muster, replete with red phone boxes, red buses and “Ello, ello, ello” bobbies on the beat tooting whistles as miscreants flee into the pea souper fog), the unlikely duo on the run from Darro and his backing conglomerate of five nations who want to get their hands on Questor and his technology. As they head into the suspiciously Californian-looking ‘British’ countryside and Robinson asks who it is that they are going to visit, Questor replies “C”. Sadly, it isn’t Stephen Fry about to make his ‘O’ face but is instead the mysterious Lady Helena Trimble (willowy German-born actress Dana Wynter of Don Siegel’s classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers), a sometime spy and courtesan who is the last recorded person to have had dealings with the absent Vaslovik. However, upon seeing the secret ‘Information Room’ that Vaslovik had installed in stately Trimble Manor – a chamber relaying coded data and secrets from all over the globe, accessible to Questor via a hairdresser’s hairdryer-looking interface device – Jerry panics and turns traitor, calling Darro with their location.

Discovering that Questor has left the premises, leaving a recorded message for him stating that he (Questor) is sorry but if he does not find his errant ‘father’ within three days then his nuclear core will go critical and then he is leaving to get away from human population centres, Robinson races after him and apologetically informs him of his turning Judas.

“You must have believed it necessary. Does that make you less my friend?” replies Questor, simply. Ouch. Straight to the heart, man. That’s up there with Capaldi’s “Do you think I care for you so little that betraying me would make a difference? from ‘Dark Water’, that is. Judas, my heart.

Their conversation occurring in a play park, Questor spots a funfair facsimile of Noah’s Ark (“An image from legend”, as he so rightly says) and suddenly the images of ships that he has been carrying in his head from the frgmentary data on the partially-deleted tapes that has caused him to inquire about “aquatic transport” all along suddenly makes sense. He knows the location of Vaslovik: Mount Ararat, and so he and Jerry head there, and into the mountain they must fall. Finally finding Vaslovik (veteran actor Lew Ayres) in a secret chamber beneath the mountain, Questor is informed by the dying man that not only is he too an android (and therefore Questor’s brother rather than father) but that they are the latest in a long line who have been on Earth for millennia with the mission to protect mankind. So here we see a similar set-up to the earlier proposed Assignment: Earth series: a not quite human hero and his human sidekick (though with the best of wishes to the man, Farrell is no Terri Garr) with access to a computerised font of all knowledge (the Information Room in Trimble Manor standing in for Gary Seven’s Beta 5 databank) standing as defenders of the Earth.

Sadly, even though Roddenberry and Trek mainstay Gene L. Coon’s script set things up neatly for the guaranteed series to come, the network’s demands (firing Farrell as a regular, and introducing a lighter tone and regular guest star love interests for the mechanical lead) were too much for Roddenberry who walked from the project. The pilot movie of The Questor Tapes aired on the 23rd of January 1974 with no more to come, though many of the ideas that would have been used for the show – an android seeking knowledge of what it is to be human, and even the gag of him informing a human female that he is “fully functional” and able to perform sexually – would be recycled for TNG.

Even though Questor was over for now, Gene Roddenberry wasn’t done. A certain long-frozen scientist was about to be revived from stasis a second time as Dylan Hunt returned on another network with a new face and the Great Bird of the Galaxy would rise again from the ashes…

(To be furthered…)

❉ ‘Genesis II’ was released on Region 1 DVD by Warner Brothers Archive Collection as a manufactured on demand DVD-R in November 2009. Available from Amazon New & Used.

❉ ‘The Questor Tapes’ was released on Region 2 DVD by Odeon Entertainment in September 2019. Available from Amazon New & Used.

❉ Glen McCulla has had a lifetime-long interest in film, history and film history – especially the genres of science fiction, fantasy and horror. He sometimes airs his maunderings on his blog at http://psychtronickinematograph.blogspot.co.uk/ and skulks moodily on Twitter at @ColdLazarou